- The Newhall House Fire -

January 10, 1883

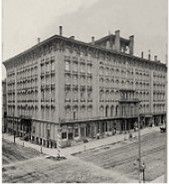

A grand banquet was held on August 26, 1857, welcoming the public to the opulent six-story hotel built by wealthy grain dealer and financier Daniel Newhall.

Situated on the northwest corner of Broadway and Michigan the house boasted 300 rooms to accommodate guests. When finished and furnished the price tag totalled

nearly $275,000 (roughly $7.5 million today). Originally the cream colored Milwaukee brick structure was surmounted by a spacious wooden cupola. The

cupola was removed following the Great Chicago Fire in an effort to reduce the risk of fire.

A grand banquet was held on August 26, 1857, welcoming the public to the opulent six-story hotel built by wealthy grain dealer and financier Daniel Newhall.

Situated on the northwest corner of Broadway and Michigan the house boasted 300 rooms to accommodate guests. When finished and furnished the price tag totalled

nearly $275,000 (roughly $7.5 million today). Originally the cream colored Milwaukee brick structure was surmounted by a spacious wooden cupola. The

cupola was removed following the Great Chicago Fire in an effort to reduce the risk of fire.

The place soon became regarded as the finest hotel west of New York. The luxurious accommodations and sumptuous dining made the Newhall House a favorite among traveling theatrical people, businessmen and politicians. Men gathered to buy and sell grain in the basement of the Newhall House, it being dubbed the "Cole-hole market." In 1859 a lanky Illinois lawyer, Abraham Lincoln, stood on a box at Newhall House to give an address. William E. Cramer, editor of the Evening Wisconsin, Charles Stanton (better known as Gen. Tom Thumb) and Ralph Waldo Emerson were among the prominent guests.

By 1883 the elegant appearance of the Newhall House was fading and, according to several sources at the time, it was "a tinder box, a fire-trap." The hotel had already had two close brushes with disaster by fire; once in 1863 and again in 1880, as well as a couple of dozen smaller blazes throughout the years. Fires had become so common at Newhall House that following the 1880 fire, Milwaukee insurance executives refused to insure the place and the owners had to seek insurance elsewhere. In the early morning hours of January 10, 1883, it came as no surprise when bells clanged in Milwaukee firehouses summoning them once again to the corner of Broadway and Michigan. Any possible thoughts of another routine run to the place were immediately dashed by the horrific scene that greeted them. Flames were leaping from the roof and some of the windows as trapped guests screamed and pleaded for help at others.

A fire discovered in the basement shot up the elevator shaft and spread out to each story, finally bursting forth onto the roof. An ordinance established following the disastrous Milwaukee fire of 1852 stated that "all outside and party walls must be made of brick or stone, or other fire-proof

material." The ordinance said nothing of the walls within a structure. The partition walls that formed the main support of Newhall House were a trestle work of twelve-inch pine lumber. Hungry flames eagerly devoured the tinder-dry timbers and, within forty-five minutes, the once grand Newhall House was a total loss.

At 5:30 a.m. the Broadway front of the building, its support timbers having been burned away, thundered to the ground as the floors collapsed upon each other. The walls at the southeast corner followed shortly after. Work began at daybreak to search the ruins, now veiled with dense clouds of steam and smoke, for remains of the victims.

A fire discovered in the basement shot up the elevator shaft and spread out to each story, finally bursting forth onto the roof. An ordinance established following the disastrous Milwaukee fire of 1852 stated that "all outside and party walls must be made of brick or stone, or other fire-proof

material." The ordinance said nothing of the walls within a structure. The partition walls that formed the main support of Newhall House were a trestle work of twelve-inch pine lumber. Hungry flames eagerly devoured the tinder-dry timbers and, within forty-five minutes, the once grand Newhall House was a total loss.

At 5:30 a.m. the Broadway front of the building, its support timbers having been burned away, thundered to the ground as the floors collapsed upon each other. The walls at the southeast corner followed shortly after. Work began at daybreak to search the ruins, now veiled with dense clouds of steam and smoke, for remains of the victims.

The hotel register was lost in the fire leaving no way to be absolutely certain how many guests were lodged at the hotel on that

tragic morning nor how many may have lost their lives, although seventy-one is the commonly accepted number of victims. Many of the bodies were burned or mangled beyond identification. On January 23rd, following services held at the Exposition Hall and St. John's Cathedral a procession of forty-three coffins, draped in black, followed routes to Forest Home and Calvary cemeteries for burial. An obelisk at Forest Home cemtery (shown left) bearing the names of the fire victims marks their final resting place.

The hotel register was lost in the fire leaving no way to be absolutely certain how many guests were lodged at the hotel on that

tragic morning nor how many may have lost their lives, although seventy-one is the commonly accepted number of victims. Many of the bodies were burned or mangled beyond identification. On January 23rd, following services held at the Exposition Hall and St. John's Cathedral a procession of forty-three coffins, draped in black, followed routes to Forest Home and Calvary cemeteries for burial. An obelisk at Forest Home cemtery (shown left) bearing the names of the fire victims marks their final resting place.

On February 5th the Coroner's jury concluded that fire was an act of arson; that the proprietors were guilty of culpable negligence for not having a sufficient number of watchmen on duty, having an insufficient number of fire escapes; that, upon previous instructions of the proprietors, the guests were not roused and the alarm not given upon discovery of the fire. In a controversial decision the grand jury found no negligence in connection with the fire. Lucius Nieman, editor of the Milwaukee Journal, accused the grand jury of whitewashing the affair and, on the front page of the Journal, sarcastically congratulated them for not indicting the fire victims for committing suicide.

- Burning of the Newhall House -

Published by the Bleyer Bros.

Cramer, Aikens & Cramer, Printers - 1883